-

サマリー

あらすじ・解説

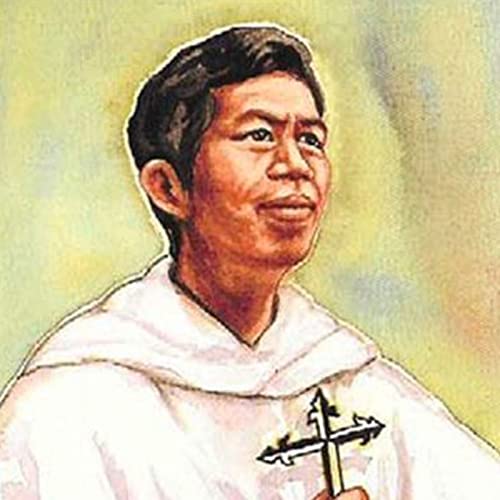

November 24: Saint Andrew Dũng-Lac, Priest, and Companions, Martyrs

1795–1839; Seventeenth–Nineteenth Centuries

Memorial; Liturgical Color: Red

Patron Saints of Vietnam

Thousands of priests and converts are hunted down, tortured, and cruelly murdered

The tide of persecution repeatedly swelled, receded, and swelled once more against today’s martyrs in various eras of Vietnamese history from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century. Matters were only slightly less brutal for Catholics living in communist North Vietnam in the twentieth century, but those victims are not included in today’s commemoration. Today’s one hundred and seventeen martyrs were beatified in four different groups, from 1900 through 1951, yet they were all canonised at the same Mass by Pope Saint John Paul II in Rome in 1988. These one hundred and seventeen include a rich mix of lay people, priests, and bishops who were mostly native Vietnamese but also include several heroic French and Spanish missionaries. Today’s martyrs each have a name and a historically verifiable narrative detailing their sad fate. Many tens of thousands more Catholics were martyred in Vietnam in this same period, yet their names are known to God alone. They will form part of that cloud of witnesses whom all the saved will one day see in heaven, wearing white robes and with a martyr’s palm in their hands.

Father Andrew Dũng-Lạc alone is named on this feast, not because his sufferings were more depraved than those of his co-martyrs, but because they were so similar. Andrew’s name is a touchstone for the entire group. Father Andrew was born to pagan parents but fell under the holy influence of a lay catechist, was baptized, became a catechist himself, entered seminary, and was ordained a diocesan priest. He was a model parish priest in every respect, and thus an ideal target once a new wave of persecution broke out. When he was first imprisoned, his parishioners raised enough money to ransom him. But about fours years later, he was arrested again, tortured, and beheaded, along with another priest, Peter Thi. The story of another of today’s martyrs, Father Théophane Vénard, made such a deep impression on the young Thérèse of Lisieux that she requested, unsuccessfully, to transfer to a Carmel convent in Vietnam.

The persecutions of the Church in Vietnam displayed characteristics similar to anti-Catholic attacks carried out in other Asian countries. In its first wave of missionaries, Catholicism’s arrival in Asia was seen as intriguing, beautiful, and new. Its priests were educated, heroic in their zeal, and culturally sensitive. Yet as its hold on the native population grew, Asian leaders became jealous and suspicious. They saw the Church either as foreign to their ancient culture’s long-established habits of life and thinking, or as an actual arm of a colonial power seeking to slowly subjugate an entire people for commercial benefit. At this historical flex point, brutal persecutions of Catholics broke out in Japan, Vietnam, and China. Yet as the Church matured over time and large native populations of Catholics survived, different persecutions, not related to colonialism, began. In the nineteenth century, Asian leaders often claimed that priests and bishops were in conspiratorial alliances with disaffected Catholic elites who sought to overthrow the reigning authorities for reasons of religion or state.

The persecution of the Church in Vietnam was outstanding for its ferocity and brutality. Asian cultures seem to excel at devising ever more brutal forms of inflicting physical and psychological pain on persecuted classes. Victims had their skin ripped off, were carefully sliced in pieces, were confined in cages hung in public squares like big cats, were compelled to trample on crucifixes, were separated from spouses and family, and often had the words “false religion” marked on their faces.

Vietnam’s communist government sent not a single representative to the canonization Mass for today’s martyrs in 1988, but thousands of Vietnamese faithful attended nonetheless, mostly from Vietnamese diaspora communities. Today Vietnam has over two thousand parishes and almost three thousand priests. Its population is about eight percent Catholic. The faith survived, even thrived, due to the exemplary witness of so many staunch disciples who did not bend to the powerful gusts that blew against them. Today’s victims bowed their heads to receive only two things—the waters of Baptism and the sword.

Martyrs of Vietnam, by your constancy and courage, help all Christians who struggle and doubt in any way to persevere in their vocations, to win the small battles over self every day, so that they can enjoy life with God and His saints one day in heaven.

1795–1839; Seventeenth–Nineteenth Centuries

Memorial; Liturgical Color: Red

Patron Saints of Vietnam

Thousands of priests and converts are hunted down, tortured, and cruelly murdered

The tide of persecution repeatedly swelled, receded, and swelled once more against today’s martyrs in various eras of Vietnamese history from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century. Matters were only slightly less brutal for Catholics living in communist North Vietnam in the twentieth century, but those victims are not included in today’s commemoration. Today’s one hundred and seventeen martyrs were beatified in four different groups, from 1900 through 1951, yet they were all canonised at the same Mass by Pope Saint John Paul II in Rome in 1988. These one hundred and seventeen include a rich mix of lay people, priests, and bishops who were mostly native Vietnamese but also include several heroic French and Spanish missionaries. Today’s martyrs each have a name and a historically verifiable narrative detailing their sad fate. Many tens of thousands more Catholics were martyred in Vietnam in this same period, yet their names are known to God alone. They will form part of that cloud of witnesses whom all the saved will one day see in heaven, wearing white robes and with a martyr’s palm in their hands.

Father Andrew Dũng-Lạc alone is named on this feast, not because his sufferings were more depraved than those of his co-martyrs, but because they were so similar. Andrew’s name is a touchstone for the entire group. Father Andrew was born to pagan parents but fell under the holy influence of a lay catechist, was baptized, became a catechist himself, entered seminary, and was ordained a diocesan priest. He was a model parish priest in every respect, and thus an ideal target once a new wave of persecution broke out. When he was first imprisoned, his parishioners raised enough money to ransom him. But about fours years later, he was arrested again, tortured, and beheaded, along with another priest, Peter Thi. The story of another of today’s martyrs, Father Théophane Vénard, made such a deep impression on the young Thérèse of Lisieux that she requested, unsuccessfully, to transfer to a Carmel convent in Vietnam.

The persecutions of the Church in Vietnam displayed characteristics similar to anti-Catholic attacks carried out in other Asian countries. In its first wave of missionaries, Catholicism’s arrival in Asia was seen as intriguing, beautiful, and new. Its priests were educated, heroic in their zeal, and culturally sensitive. Yet as its hold on the native population grew, Asian leaders became jealous and suspicious. They saw the Church either as foreign to their ancient culture’s long-established habits of life and thinking, or as an actual arm of a colonial power seeking to slowly subjugate an entire people for commercial benefit. At this historical flex point, brutal persecutions of Catholics broke out in Japan, Vietnam, and China. Yet as the Church matured over time and large native populations of Catholics survived, different persecutions, not related to colonialism, began. In the nineteenth century, Asian leaders often claimed that priests and bishops were in conspiratorial alliances with disaffected Catholic elites who sought to overthrow the reigning authorities for reasons of religion or state.

The persecution of the Church in Vietnam was outstanding for its ferocity and brutality. Asian cultures seem to excel at devising ever more brutal forms of inflicting physical and psychological pain on persecuted classes. Victims had their skin ripped off, were carefully sliced in pieces, were confined in cages hung in public squares like big cats, were compelled to trample on crucifixes, were separated from spouses and family, and often had the words “false religion” marked on their faces.

Vietnam’s communist government sent not a single representative to the canonization Mass for today’s martyrs in 1988, but thousands of Vietnamese faithful attended nonetheless, mostly from Vietnamese diaspora communities. Today Vietnam has over two thousand parishes and almost three thousand priests. Its population is about eight percent Catholic. The faith survived, even thrived, due to the exemplary witness of so many staunch disciples who did not bend to the powerful gusts that blew against them. Today’s victims bowed their heads to receive only two things—the waters of Baptism and the sword.

Martyrs of Vietnam, by your constancy and courage, help all Christians who struggle and doubt in any way to persevere in their vocations, to win the small battles over self every day, so that they can enjoy life with God and His saints one day in heaven.